Digital Fragments in Physical Space: On Andy Boot’s Sculptures

Vivien Trommer

What is a work of art? What is creativity? Why do we believe in the value of art? Today, everyone is creative, whether involved in economics, science, or art. The only difference between working as an artist and most other professions is that artists do not receive a monthly income or regular payment. Otherwise, artists go about their daily working routine much like any other professional: they meet with clients and contractors, they negotiate with partners, they instruct their assistants, and they communicate their goals. So what makes their output so different? What is the value we find in a work of art?

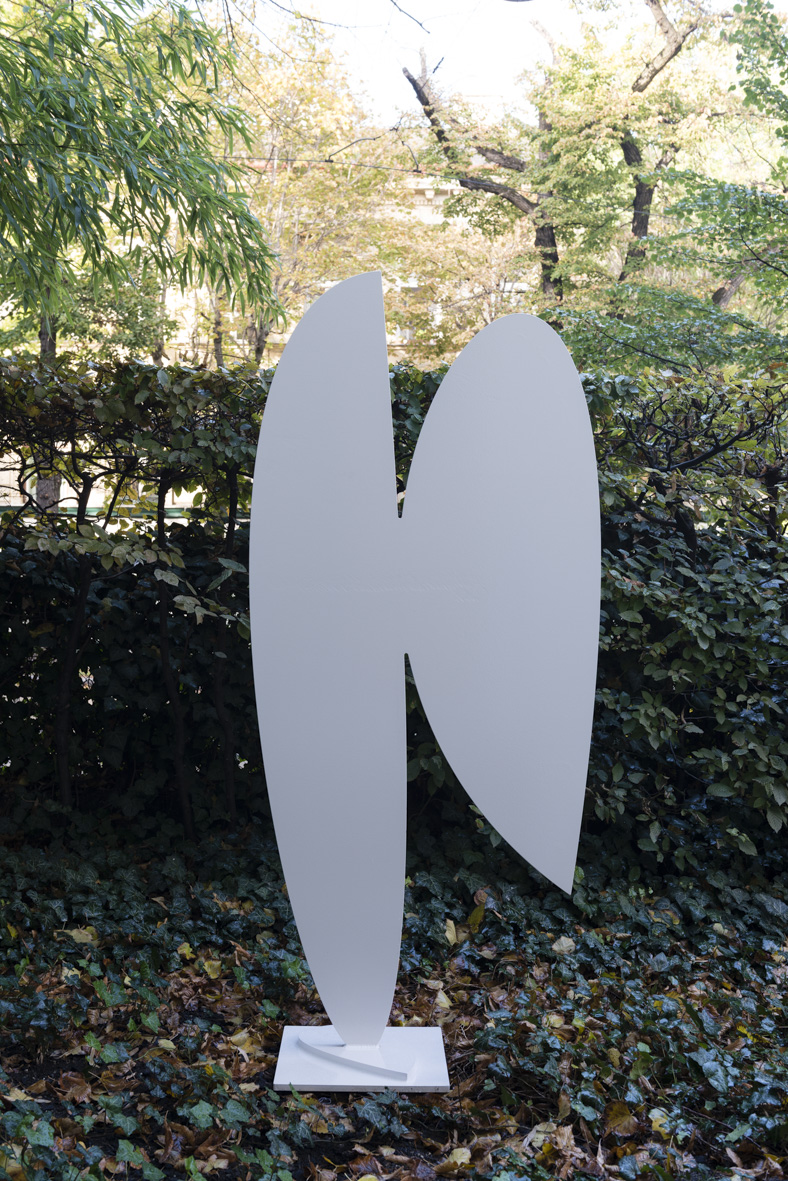

Take Andy Boot’s Untitled (2016),

a white-coated steel sculpture permanently installed at the 21er Haus sculpture garden in Vienna. The work is the shape of an abstract image. It seems to have fallen from the sky and landed in the garden, becoming an object-like thing that can be walked around or even crawled through. Its wobbly, rounded-off shapes touch the ground on as few points as possible, fostering the impression that the work is featherlight and floats in space, unimpressed by gravity. A horizontal fold into two flat sides provides strength, so that it supports itself only through its own inert forces. In sculptural terms, the work elaborates on mass and balance to form a freestanding object that is neither a flat painting nor a solid sculpture. It has a certain similarity to Ellsworth Kelly’s first two welded sculptures Gate

and Pony (both 1959), made from painted aluminum, exemplifying what Gottfried Boehm has aptly pointed out as Kelly’s innovation in art history: eluding “painting when he creates a painting, just has he eludes relief and sculpture when he makes use of their possibilities.” 1 Although he would still abide by the terms painting, relief, and sculpture solidified by modernism, Kelly explored the relations between these fields and therefore anticipated the sixties discourse on medium specificity. Boot’s sculpture on the other hand takes up Kelly’s pre-minimalist ideas, investigating the current notions of color and form as paradigms for both painting and sculpture. However, it would be misleading to read Boot’s Untitled as a remake; rather, his work performs an ironic revision of modernist sculpture—a revision of its look, methods of production, and theory.

a white-coated steel sculpture permanently installed at the 21er Haus sculpture garden in Vienna. The work is the shape of an abstract image. It seems to have fallen from the sky and landed in the garden, becoming an object-like thing that can be walked around or even crawled through. Its wobbly, rounded-off shapes touch the ground on as few points as possible, fostering the impression that the work is featherlight and floats in space, unimpressed by gravity. A horizontal fold into two flat sides provides strength, so that it supports itself only through its own inert forces. In sculptural terms, the work elaborates on mass and balance to form a freestanding object that is neither a flat painting nor a solid sculpture. It has a certain similarity to Ellsworth Kelly’s first two welded sculptures Gate

and Pony (both 1959), made from painted aluminum, exemplifying what Gottfried Boehm has aptly pointed out as Kelly’s innovation in art history: eluding “painting when he creates a painting, just has he eludes relief and sculpture when he makes use of their possibilities.” 1 Although he would still abide by the terms painting, relief, and sculpture solidified by modernism, Kelly explored the relations between these fields and therefore anticipated the sixties discourse on medium specificity. Boot’s sculpture on the other hand takes up Kelly’s pre-minimalist ideas, investigating the current notions of color and form as paradigms for both painting and sculpture. However, it would be misleading to read Boot’s Untitled as a remake; rather, his work performs an ironic revision of modernist sculpture—a revision of its look, methods of production, and theory.But what do we mean when we call an object a “sculpture”? A brief glance at history might be illuminating here. In the early twentieth century, artists like Constantin Brâncuși, Marcel Duchamp, Naum Gabo, Alberto Giacometti, Barbara Hepworth, and Alexander Rodchenko, among many others, introduced what we now perceive as modernist sculpture, superseding the ancient Greek ideal depicting human figures, mostly in the gestalt of God and heroes. Made from new materials such as steel, glass, or scrap ingredients, modernist sculpture freed itself from figuration and, in the wave of the avant-garde, became abstract, cubist, constructivist, Dadaist, futurist, kinetic, surrealist—in any case an autonomous work of art. As Rosalind Krauss noted in retrospect, modernism succeeded in not only inventing the readymade, revisiting the logic of the monument, but also in introducing the synthesis of statue and pedestal.2 In late modernism, however, Ad Reinhardt still defined sculpture as “something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.” 3

It was only in the early sixties—when trained painters like Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, along with sculptors like Carl Andre and Anne Truitt, began to experiment with three-dimensional forms—that sculpture was suddenly given a boost in the US and for a short period of time surpassed painting as the highest form of art. Judd, however, took a radical line and announced that his “specific objects” were “neither painting nor sculpture,” 4 thus severing the ties to previous developments in European sculpture—at least from his perspective. Two years later, in 1967, Robert Morris classified minimal sculpture further and stated—and this was new—that it is made from “industrial and structural materials [which] are often used in their more or less naked state,” 5 and also mostly outside the artist’s studio in professional factories. Fostered by claiming the manufactured geometric cube as sculpture’s new paradigm, Minimal Art quickly became an acknowledged and institutionalized theory and praxis.

With the rise of the Internet and digitization, sculpture underwent its latest radical shift at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Innovations such as 3-D scanning, laser-cutting, or the use of synthetic materials are being explored by artists like Boot, Aleksandra Domanović, Oliver Laric, Mark Leckey, and Pamela Rosenkranz. Digitization, moreover, has had a major impact on processes of artistic research, as David Joselit recently observed: “what matters most is not the production of content, but its retrieval in intelligible patterns through acts of reframing, capturing, reiterating, and revealing.” He concludes that today knowledge is produced “through the aggregation, rather than the production of content.” 6 Having said that, assembling data and information became an integral part of artistic production and clearly had a remarkable influence on contemporary sculpture.

It might seem like a lengthy and yet incomplete journey to recall the achievements in the field of sculpture made during the last century, but all the mentioned shifts offer great tools for a better understanding of Andy Boot’s endeavor. At the core, his investigations incorporate questions about sculpture’s history and its medium-specificity, its engagement with new materials and technologies, and explore its real and virtual quality in times of image and data explosion. Working with new digitized methods of research and production—something that might not be obvious at first glance—Boot deeply reflects on today’s notion of sculpture. It seems essential that we look back at how the steel sculpture Untitled (2016),

mentioned above, was made. Part of the broader series Cosmic Latte, the work is based on scientific research conducted by the astronomers Karl Glazebrook and Ivan Baldry at Johns Hopkins University, who studied and calculated star formation around the year 2000. As a byproduct of their survey, they detected the average color of the universe while measuring the spectral range of light from about 200,000 galaxies. At first, they determined that the color is mint green before, two months later in March 2002, they found out that it comes closer to a soft vanilla beige, almost a white.7 The study made it into the Washington Post, where Glazebrook jokingly announced that he was still searching for the color’s perfect name. Peter Drum, who read the article at Starbucks while having his daily latte, glanced at the color displayed in the newspaper, then back at his half-empty coffee cup, and dubbed it Cosmic Latte.8 Out of all the suggestions submitted, the team of scientists voted for Drum’s idea and thus a new color was born, which immediately got its own sRGB and Hex triplet codes. Amused by the story and provided with these codes, Boot started to search the Internet for Cosmic Latte-colored images. Adopting methods the scientists used, he identified the hue in random online images to then excise creamy beige color fields using Photoshop. Subsequently, he zoomed in on the cutouts, and with the Simplify algorithm, evened and smoothed all the rough edges, ending up with abstract images in perfectly rounded off shapes. The next step was to turn these virtual sourced images into real beings floating around like stars in galaxies. Having the outlines printed and laser cut in standard MDF with a matte-white paper coating, Boot started to assemble and nail the single shapes together, added a foot or pedestal-like support here and there, and transformed the two-dimensional images into flat freestanding objects elaborating on gravity and balance.

mentioned above, was made. Part of the broader series Cosmic Latte, the work is based on scientific research conducted by the astronomers Karl Glazebrook and Ivan Baldry at Johns Hopkins University, who studied and calculated star formation around the year 2000. As a byproduct of their survey, they detected the average color of the universe while measuring the spectral range of light from about 200,000 galaxies. At first, they determined that the color is mint green before, two months later in March 2002, they found out that it comes closer to a soft vanilla beige, almost a white.7 The study made it into the Washington Post, where Glazebrook jokingly announced that he was still searching for the color’s perfect name. Peter Drum, who read the article at Starbucks while having his daily latte, glanced at the color displayed in the newspaper, then back at his half-empty coffee cup, and dubbed it Cosmic Latte.8 Out of all the suggestions submitted, the team of scientists voted for Drum’s idea and thus a new color was born, which immediately got its own sRGB and Hex triplet codes. Amused by the story and provided with these codes, Boot started to search the Internet for Cosmic Latte-colored images. Adopting methods the scientists used, he identified the hue in random online images to then excise creamy beige color fields using Photoshop. Subsequently, he zoomed in on the cutouts, and with the Simplify algorithm, evened and smoothed all the rough edges, ending up with abstract images in perfectly rounded off shapes. The next step was to turn these virtual sourced images into real beings floating around like stars in galaxies. Having the outlines printed and laser cut in standard MDF with a matte-white paper coating, Boot started to assemble and nail the single shapes together, added a foot or pedestal-like support here and there, and transformed the two-dimensional images into flat freestanding objects elaborating on gravity and balance.Initially in 2013, seven of these low-profile sculptures were presented at Galerie Emanuel Layr in Vienna. Either lying on the floor or standing up straight, they formed a sculpture garden full of modernist compositions and formations. Most of the works, all untitled, including this one (2013),

look like weird comic characters, others take the shape of an Ellsworth Kelly relief, or speak of gravity in a sense. For the show the gallery walls were painted in a slightly Cosmic Latte hue, disguising the space as a zero gravity zone. Eventually, in 2016, the series underwent its next step and a group of different shapes was cut in white-coated steel. Among the works was Untitled,

look like weird comic characters, others take the shape of an Ellsworth Kelly relief, or speak of gravity in a sense. For the show the gallery walls were painted in a slightly Cosmic Latte hue, disguising the space as a zero gravity zone. Eventually, in 2016, the series underwent its next step and a group of different shapes was cut in white-coated steel. Among the works was Untitled,  which is installed like the other steel works in public parks or private gardens. They can be perceived as another outcome of this ongoing series, following the same parameters of research.

which is installed like the other steel works in public parks or private gardens. They can be perceived as another outcome of this ongoing series, following the same parameters of research.Above all, it seems obvious that Boot shares formal interests with abstract sculptors and, in a slightly ironic fashion, reflects on the traditional modes of sculpture—its volume, line, texture, color, and appearance in space. But unlike modernist sculptures, his shapes are deployed with digital programs, handed over to commercial factories, where they are converted into objects manufactured from industrial materials using new cutting and carving techniques, and assembled in his studio. His working process embraces chance as much as it makes use of strategic systems and seems to come close to a combination of different theories and praxes on something we have been calling sculpture for about 120 years. Instead of appropriating just the latest look, Boot questions the image quality of sculpture by testing its virtual and physical appearances.

Still, there is something ambiguous about Boot’s works. If we compare the Cosmic Latte series with another series called C C,

which was presented at Croy Nielsen in Berlin in 2014, we might think they look so different that the same artist could not have made them, just because the formal differences in these works are quite distinct. Or is there a common ground—a shared logic—that is there but difficult to discern?

which was presented at Croy Nielsen in Berlin in 2014, we might think they look so different that the same artist could not have made them, just because the formal differences in these works are quite distinct. Or is there a common ground—a shared logic—that is there but difficult to discern?C C

is a series of sculptures in three parts. The first is a pedestal, a minimal construction of black-polished metal that reaches to about belly-height. On its surface, concrete cubes of individual shapes are presented, from which thin metal mesh, coated with colorful prints in violet, bright-blue, or turquoise hues, ripple out into the air. Depending on the angle from which the sculptures are viewed, a dizzying moiré effect shimmers over the planes of the mesh fully exposing their anti-form aesthetic, and contrasting the rigor of their supports.

is a series of sculptures in three parts. The first is a pedestal, a minimal construction of black-polished metal that reaches to about belly-height. On its surface, concrete cubes of individual shapes are presented, from which thin metal mesh, coated with colorful prints in violet, bright-blue, or turquoise hues, ripple out into the air. Depending on the angle from which the sculptures are viewed, a dizzying moiré effect shimmers over the planes of the mesh fully exposing their anti-form aesthetic, and contrasting the rigor of their supports.Visually, they resemble Isa Genzken’s architectural models Halle and Saal (both 1987), concrete works on steel tube stands that she started a decade after having worked on painted wooden sculptures, Ellipsoids and Hyperbolos, that either lay on the floor or are freestanding. Introducing the plinth back into the realm of sculpture, Genzken, as curator Beatrix Ruf has noted, challenges the autonomy of sculpture as a legacy of modernism:

Isa Genzken placed the next group of works of painted and unpainted plaster (from 1984 on) on a plinth, which served to raise the sculpture, the object ... to the public’s eye level. A technique Isa Genzken adopted for many of her subsequent work groups without, however, having herself any interest in classical plinth sculpture, but that referred to the functions of the transformation and autonomy that she attaches to the art object.9

It was Brâncuși who anticipated the discourse on the synthesis of pedestal and sculpture. Since 1910, he preferred his marbles or bronzes to be shown as multipart works, including plinths that were designed specifically to fit each sculpture.10 Boot reactivates and combines shorter versions of Genzken’s stands with Brâncuși’s method to touch upon and emphasize questions of display and modes of presentation that lay within the presence of sculpture. Following formal criteria, C C can be perceived as an investigation into the effects of exhibiting and presenting works of art, questions which have been key for sculptors since early modernism, and today are discussed by artists like Thea Djordjadze, Vincent Fecteau, and Rachel Harrison.

However, looking closer at C C’s subject matter, it turns out that it speaks of a freaky Internet phenomenon—like the Cosmic Latte series. It looks into GeoCities, a free web-hosting platform for personalized homepages that peaked at the end of the nineties prior to Myspace and Facebook. Originally founded in 1994 by David Bohnett and John Rezner, it was acquired by Yahoo! five years later in 1999. Today it is only active in Japan due to a shutdown of the United States GeoCities service on October 26, 2009, when approximately 38 million pages were lost. In its early stage, GeoCities offered a novel directory and was organized as neighborhoods with names like “Heartland,” hosting websites for parenting and family; “South Beach,” presenting pages for a hip spot to hang out, for seeing and being seen; or “Paris,” where subjects like romance, poetry, and the arts were welcomed. During the sign-in process, new members chose the district in which their site should belong. The neighborhood’s name plus a unique number then formed the web address, hence it was location that mattered in this network.11 In homage, Boot’s sculptures carry the neighborhood’s names and as such are titled Heartland (CASA DE DAVI) 1, (2014)

Heartland (CASA DE DAVI) 2, 2014

Heartland (CASA DE DAVI) 2, 2014

and Paris (cybertrips) 1 (2014)

Clearly, GeoCities belonged to an era when websites were still a creative tool and not just a commercial instrument. Its layout was the special feature: a full-screen picture as background on which texts and some fancy GIFs were arranged, so members needed to know a bit of HTML coding to design their own pages. It comes as no surprise that some enthusiasts recently launched a web archive project to rescue and maintain some of the lost websites.12 Stumbling across this collection of defunct sites, Boot was intrigued by their simplicity and creativity and six pages became an integral part of the creation of his C C

sculpture series. Printed on the mesh are backgrounds—GeoCities’s unique feature—that either come about as colorful patterns or as thematic pictures.

In a way, Boot creates an impetus to remember GeoCities and transfers its story from the depths of the Internet into physical space. Displayed as an archive of personalized homepages, C C forms an exhibition of art objects that resemble small tombstones and monuments, thereby creating something like a memorial site that newly defines sculpture’s contemporary realms.

Ina Blom has written that “new media and information technologies are themselves objects of thinking, investigation, and imagination.” This thought encourages her to argue for a need to conceptualize contemporary art’s “double relation to, on the one hand, technological media and the realm of media production and, on the other hand, the notion of the artistic medium.” 13 She concludes that the human body that senses the effects of digital information has become the medium in contemporary art. With that in mind, Boot’s C C and Cosmic Latte

series test the relation between two-dimensional images, sourced from the Internet as just a chain of data, and the bodily experience of their three-dimensional counterparts in real space. They do this by pretending to follow the features of modernist sculpture—three-dimensionality, plasticity, multi-perceptivity, and bodily experience. In short, both series investigate the notions of the image, sculpture, and space—the work of art—in the digital age.

series test the relation between two-dimensional images, sourced from the Internet as just a chain of data, and the bodily experience of their three-dimensional counterparts in real space. They do this by pretending to follow the features of modernist sculpture—three-dimensionality, plasticity, multi-perceptivity, and bodily experience. In short, both series investigate the notions of the image, sculpture, and space—the work of art—in the digital age.Finally, coming back to the question of art and its value, it seems striking how today works of art engage in the dynamics of our knowledge. Information, in the current times of data explosion and technological innovation, is mostly pooled on servers and external hard drives, and will only be accessible as long as these systems are accessible (see the GeoCites example). Thinking, as suggested by Boot, about the transformation of digital data into physical space is a mechanism for cultural preservation and its vitality, a form of archeology. This is where art’s value can be recognized; in the creation of meaningful objects that speak about our culture and that, preserved and promoted in museums, can be passed on to future generations. Art captures a certain zeitgeist. It is able to preserve valuable moments of our time, protects the past from vanishing and disappearing, and makes information accessible. Andy Boot’s practice thus provides a way to keep our knowledge alive.

Notes

-

Gottfried Boehm, “In-Between

Spaces: Painting, Relief, and

Sculpture in the Work of

Ellsworth Kelly,” in Ellsworth

Kelly: In-Between Spaces,

Works 1956–2002, exh. cat.

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/

Basel (Berlin, 2003), p. 19.

-

Rosalind E. Krauss, “Sculpture

in the Expanded Field,” in October (Spring 1979), p. 34.

- Quoted after a statement at a dinner in the late fifties in Lucy R. Lippard, “As Painting is to Sculpture: A Changing Ratio,” in American Sculptures of the Sixties, edited by Maurice Tuchman, exh. cat. Los Angeles County Museum (Los Angeles, 1965), p. 31.

-

Donald Judd, “Specific

Objects,” in Donald Judd Writings, edited by Flavin Judd

and Caitlin Murray (New York

and London, 2016), p. 135.

-

Robert Morris, “Notes on

Sculpture, Part 3: Notes and

Non Sequiturs” in Continuous

Project Altered Daily: The

Writings of Robert Morris, An

October Book (Massachusetts

and London, 1995), p. 28.

-

David Joselit, “Conceptual

Art 2.0” in Contemporary Art: 1989 to the Present, edited by Alexander Dumbadze and Suzanne Hudson (New Jersey, 2013), p. 160. -

Michael Purdy, “Astronomers

Determine Color of the Universe,” last modified

January 10, 2002, http://

pages.jh.edu/news_info/

news/home02/jan02/color.

html (accessed July 22, 2017);

and the press release update,

Michael Purdy, “Astronomers

Determine Color of the

Universe,” last modified March

7, 2002, http://pages.jh.edu/

news_info/news/home02/

mar02/color.html (accessed

July 22, 2017).

-

“Cosmic Latte,” Wikipedia, last

modified April 24, 2017, http://

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmic_

latte (accessed July 21, 2017

-

Beatrix Ruf, “Contact” in Isa

Genzken, edited by Veit Loers

and Beatrix Ruf, exh. cat.

Kunsthalle Zurich and Museum

Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach

(Cologne, 2003), p. 11.

-

Nina Gülicher, Inszenierte

Skulptur: Auguste Rodin,

Medardo Rosso, Constantin

Brancusi (Munich, 2011), pp.

133–42.

-

“Yahoo! GeoCities,” Wikipedia,

last modified June 25, 2017,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Yahoo!_GeoCities (accessed

July 31, 2017).

-

http://www.geocities.ws/

archive/.

- Ina Blom, “Inhabiting the Technosphere: Art and Technology Beyond Technical Innovation” in Contemporary Art: 1989 to the Present, edited by Alexander Dumbadze and Suzanne Hudson (New Jersey, 2013), p. 149.

On Carpets and Commands

Barbara Casavecchia

This text originates from a series of chats on Skype and FaceTime, regularly interrupted by Andy Boot’s dog, who started to bark or walked into the studio, only to get himself walked out, hence generating minor gaps in the conversation’s flow. Each time, Andy would turn to his invisible (for me) companion and softly repeat: “Platz, platz”. Calm would ensue. Humans too, are well-trained creatures, like horses for dressage, or Pavlov’s dogs. Pushy algorithms and compulsive online life has taught us to perform simple and repetitive exercises at controlled speed. By the millions, we willingly react to the lures of efficiency and urgency, the forcibly exchanged niceties, the kick of immediate response, its endless novelty, with neurotransmitters running high. We need to be walked out of the arena of information overload, from time to time. We crave slowness and breaks; we’re stressed out, we bark.

Boot e-mailed me: “I suppose an overload suggests an awareness or reaching a point from mass. I think one form could be subtler than that: perhaps an information overload is a filter bubble, or based off collected meta data slowly dripping on stone to make a dent. And maybe our parameters for measuring an information overload are too extreme. Wouldn’t it also be an overload if we are rewired to receive serotonin from our news feeds and ‘likes’?”

The rewiring is exhausting. “The once fabulous aura that surrounded our beloved apps, blogs, and social media has [been] deflated. Swiping, sharing, and liking have begun to feel like soulless routines, empty gestures,” comments Geert Lovink on e-flux journal. “To put it in spatial terms, cyberspace has turned out to be a room containing a house containing a city that has collapsed into a flat landscape in which created transparency turns into paranoia. We’re not lost in a labyrinth but rather thrown out into the open, watched and manipulated, with no center of command in sight.” A stressful condition indeed for domesticated animals.

In his youth, Boot was fond of GeoCities, which was a site launched in the mid-nineties by a small Californian start-up, and quickly became one of the most visited websites on the global scale. It was built as a group of “cities” and neighborhoods that could be navigated by users, and by accepting the bargain of fifteen megabytes for free (plus ads), they could become residents and design and construct their own homepages—another definition borrowed from the pervasive vocabulary of architecture and dwelling. Users could use stock fluo colors, lo-res GIFs, and Flash animations (which Boot took as source material for C C, his 2014–15 collection of sculptures) for their designs. The directories of user-generated content were then archived by subject and named accordingly, so that Athens aggregated everything related to culture and literature, Vienna to classical music, and so on. In 1999, GeoCities turned into a case study for the age of the dot-com bubble: after reaching its first million members, it was acquired by Yahoo! for 5.6 billion dollars, just to collapse right afterwards because of a (creative) class action. As soon as the provider tried to increase its margins of profit by capitalizing on the rules for “inhabiting” the infrastructure, GeoCities’ netizens flocked away en masse, refusing both to pay for the service, as well as to conform to the new standard formats introduced for the profiles. The exodus marked the collapse of a vast social network erected, for the first time, on the voluntary contributions of its content generators. The digital “cities” quickly turned into “ruins” (as Olia Lialina defines their lost or broken webpages) and vacant lots, like abandoned shopping malls, or contemporary ghost cities like the Inner Mongolian city of Ordos (which means “palaces” in Mongolian), whose industrial park currently hosts one of the world largest Bitcoin mines, run by the Chinese IC design company Bitmain Tech Ltd.

Only fragments of the original GeoCities (closed in 2009) remain, as junkspaces—frozen digital fallout of modernization in progress. “Like digital waste, or a museum, in a way,” Boot says. In its current, archived version, GeoCities works as a memento of the years when the public library and its indexical paradigm, instead of the private album and its erratic chronology, were the favorite template of information communities, an era when users would proactively share their knowledge, instead of their picture-perfect individual lifestyle and likes, dished out as readymade fields for data extraction.

How to tame information, to control its flow, and assign it a reasonable place is a vital necessity for those living under the rule of the networked condition. When Boot puts things, shapes, and images into place with his works, his “Platz, platz” seems whispered with a healthy dose of self-reflective irony. I imagine his untitled series of rhythmic gymnastics colored ribbons immobilized by wax, as tongue-in-cheek portraits of our carefully choreographed routines in front of a screen—the more well rehearsed, the less self-aware.

He turned his fascination for junk e-mails and their surreal, broken language into a scanner of our daily bouts of blind consumption. Maybe it’s only by starting from the margins of mindfulness, by starting from what is specifically built in order to be ignored, overlooked, and easily done away with that one can understand imperceptible trajectories and paths. By slowing down the process, and focusing on apparently worthless fragments of basic spam, Boot brings center stage the lapsus (the slip, the error, the lapse) of our digital unconscious. If digital devices are now perceived as extensions of self, why shouldn’t they also affect the self’s own perception and our increasingly intimate relationship with the ambivalent messages we receive from them?

“I think one of the points of looking at junk e-mails is that they are things that operate on a daily basis,” Boot says. “My thought was: if you’re getting this so many times every day, could this have an impact on your psyche, or possibly on your relationships? As if they were raindrops falling on your head.” With his ongoing series of carpets—started in 2012, and currently including eleven works—he isolates, magnifies, and reintroduces the aesthetic realm of geometric abstraction from the rubble of words and images that were originally morphed and distorted in order to trick both human and machinic gestalt. With the carpets, Boot has had a digitally handcrafted image manually re-crafted in order that it might operate as a “poor image” (to use Hito Steyerl’s phrase)—a lo-res image which is nonetheless powerful enough to be acknowledged, to redefine the hierarchies between subject and background, center and margins, text and visual communication, and to subtract itself from policing, censorship, and control exercised by filters and firewalls.

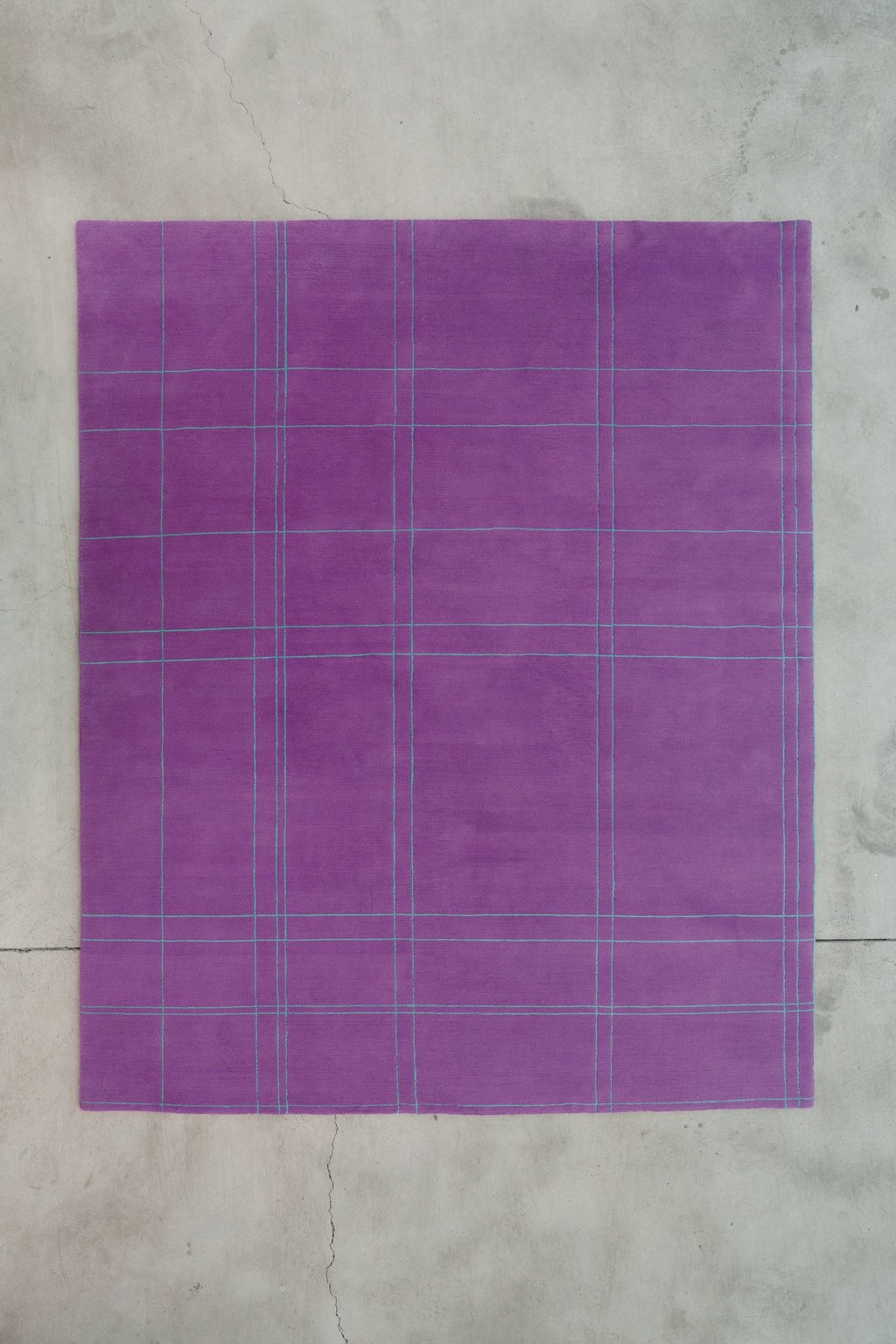

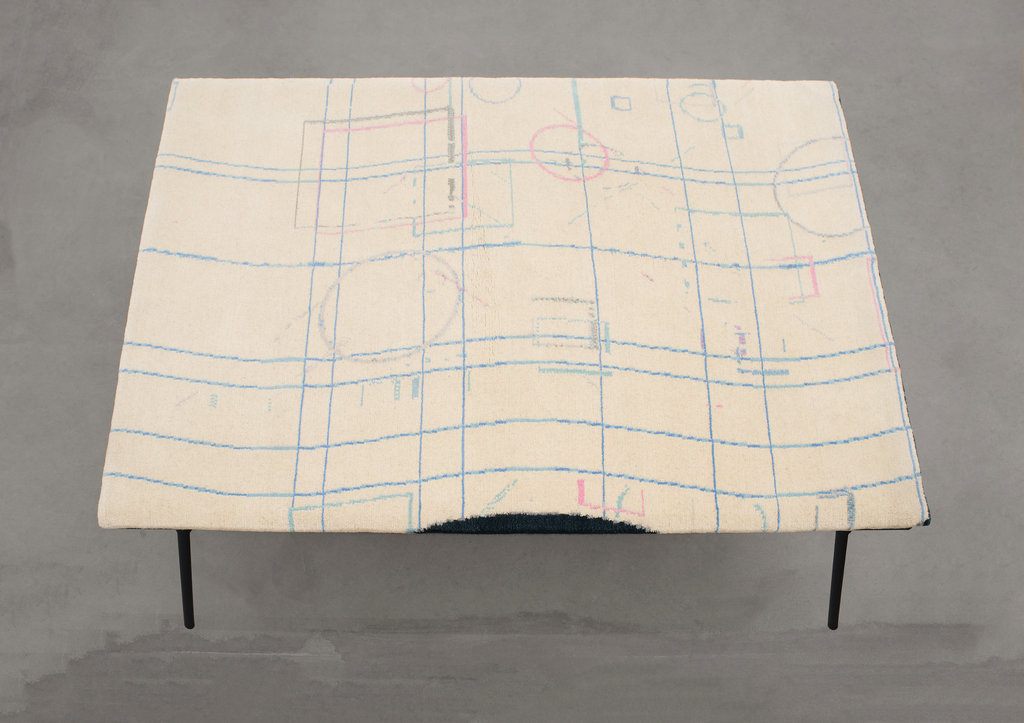

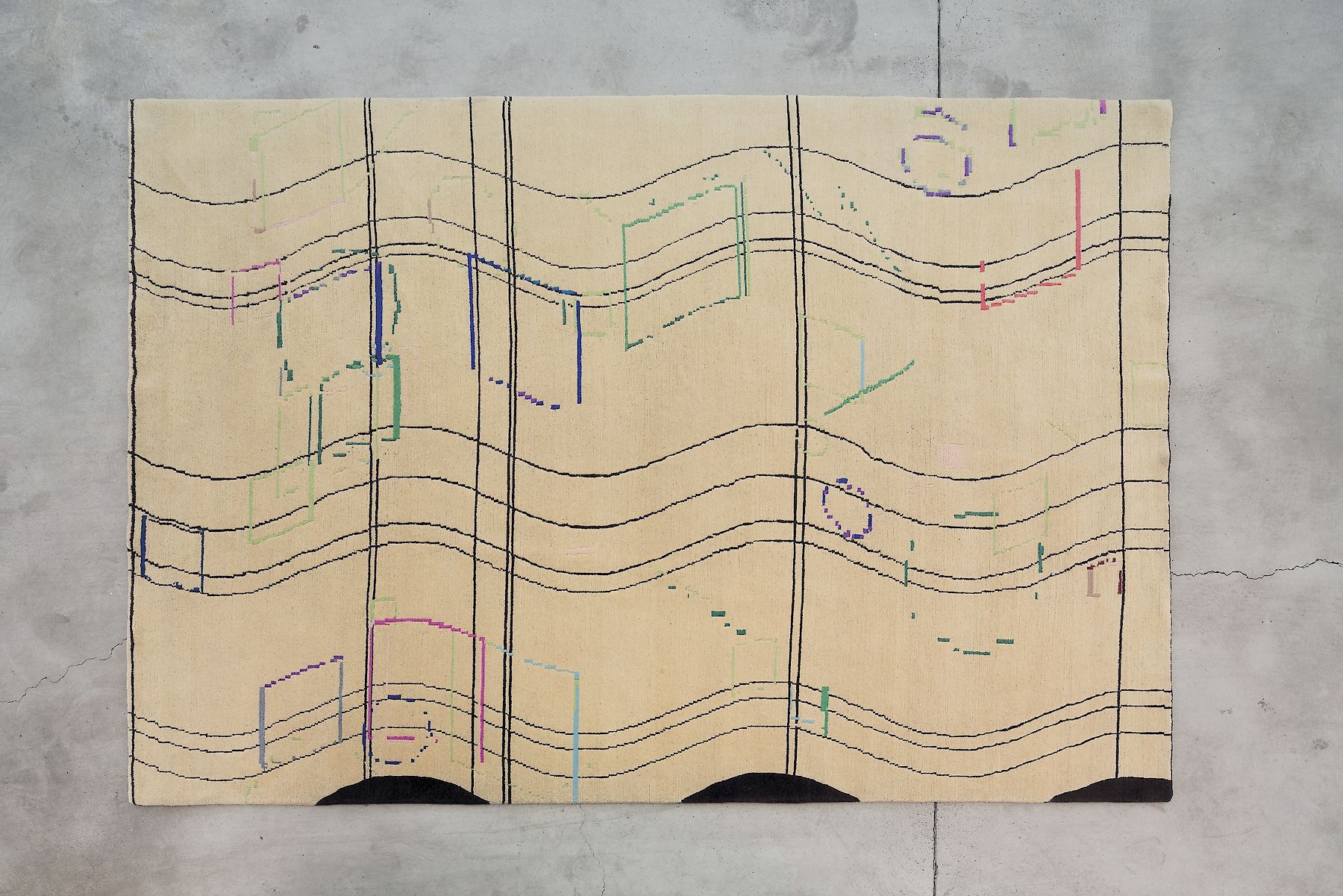

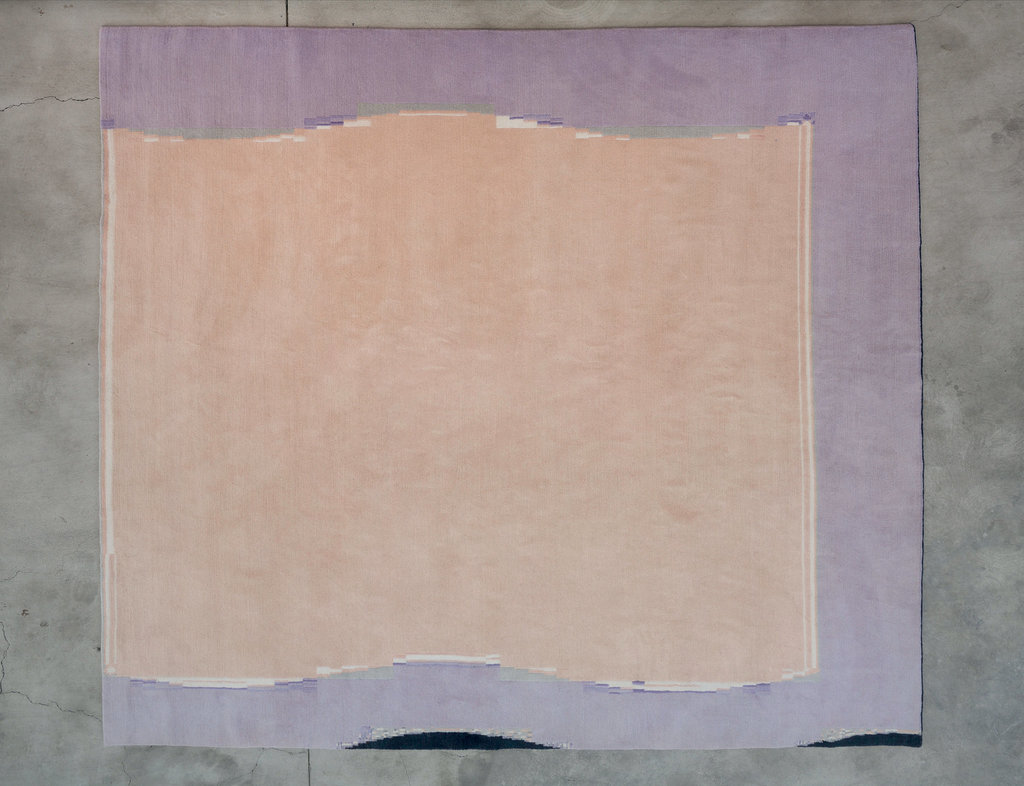

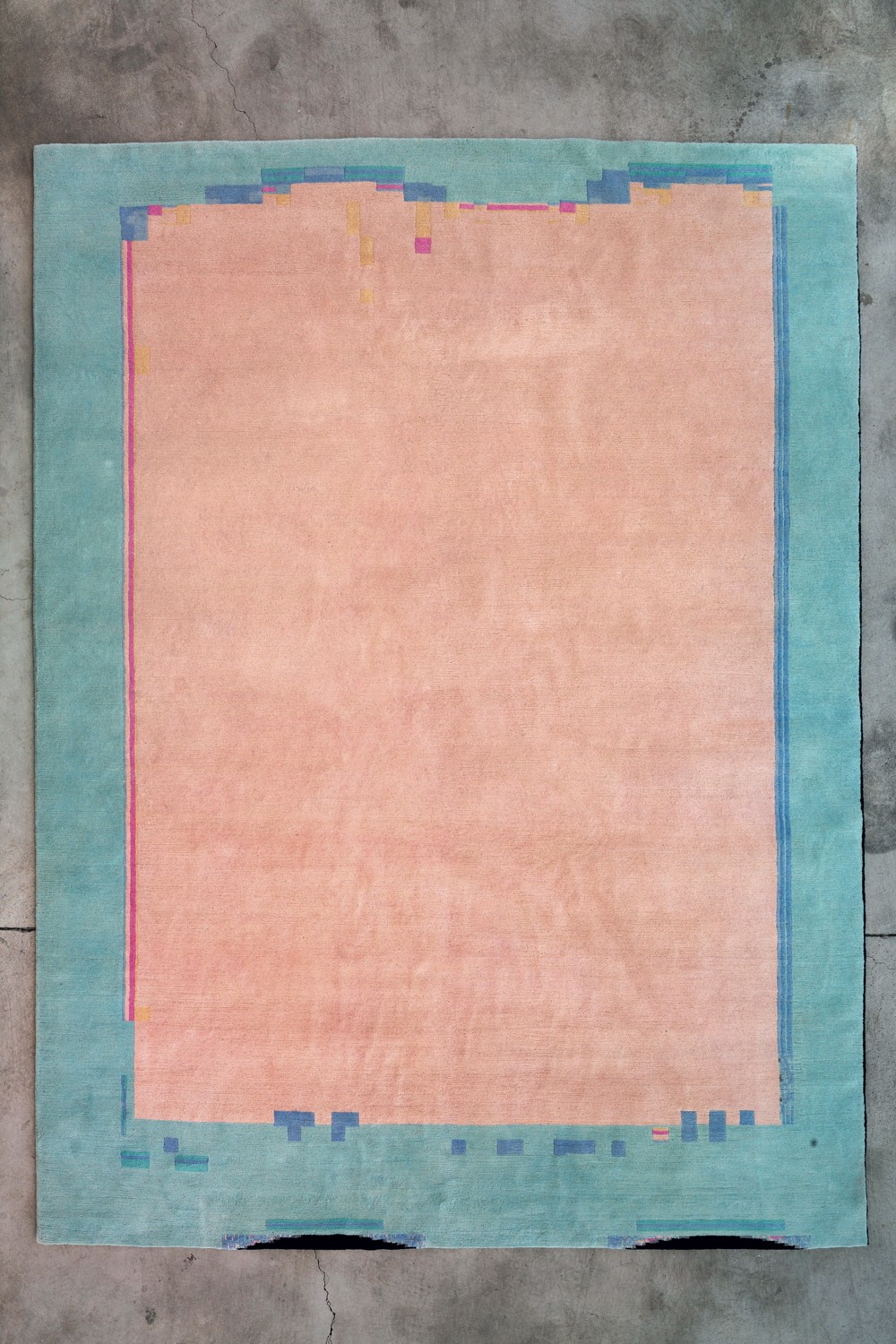

The titles of the carpet works, such as Trombone (2012),

Submits (2012),

Submits (2012),  980(2013),

980(2013),  ineffectual (2013),

ineffectual (2013),  scalping (2013),

scalping (2013),  inviolable (2014),

inviolable (2014),  tackily(2014),

tackily(2014),  gladding (2014)

gladding (2014)  replicate the original subject headings of junk mails, the labels assigned to the jpegs of their files, or the graphics’ full names. Once turned into elegant, hand-tufted, and hand-knotted wool carpets, those images successfully make their way again into the intimacy of our private, domestic sphere, so that they can finally fulfill their initial goal. Boot closes the circle by explaining that he thinks “they are strongest when there are people living in the same space”—the quintessential stock image of the happy (post-digital) family.

replicate the original subject headings of junk mails, the labels assigned to the jpegs of their files, or the graphics’ full names. Once turned into elegant, hand-tufted, and hand-knotted wool carpets, those images successfully make their way again into the intimacy of our private, domestic sphere, so that they can finally fulfill their initial goal. Boot closes the circle by explaining that he thinks “they are strongest when there are people living in the same space”—the quintessential stock image of the happy (post-digital) family.While discussing the carpets, their conceptual framing, and their actual making (they are manufactured in Kathmandu, Nepal, from large Illustrator files sent by the artist, who discusses with the local producer the choice of colors on the basis of the standard Pantone palette), Boot pointed out to me a key reference from Michel Foucault’s “Des Espaces Autres” (Of Other Spaces, 1967) where he describes the carpet as a hortus conclusus, a paradisiac garden, as well as a heterotopia. “The garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space,” Foucault writes. In the same essay, the French author also remarks that “We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.”

We call it the Web, nowadays, and Boot’s carpets mirror its experience. If the first Industrial Revolution had the loom as its totem, as the ideal tool for mass manufacturing textile goods at unprecedented speed, in the present time the keyboard and the touchpad have taken on the loom’s role as mass workbenches for manufacturing an endless flow of content, images, information, and data that informs the Web and our days. The contemporary notions of free time, of voluntary labor, and even of the “working classes” are still under (re)construction, like broken “threads.” And if, as Beatriz Colomina explained, our beds have become our offices, then the carpet is another perfectly comfortable item of domestic furniture where we can work 24/7.

Back in the 1960s, avant-garde groups such as Mono-ha and Arte Povera supported the idea of a “poor” art as a form of radical rejection of consumerism, its manic consumption pace, and the obsession for new, aptly fetishized media. It worked as an attempt to redeem old things annihilated by new technologies, as well as an attempt to “hack” them. “First came man, then the system. That is the way it used to be. Now it’s society that produces, and it’s man that consumes” was the incendiary incipit of the manifesto “Arte Povera: Notes for a Guerrilla War,” signed by Germano Celant and published in Flash Art in 1967. A current synonym for “poor” is “plain” or even “dumb,” as an intended opposition to “smart.” Very often Boot has used “poor” materials for his sculptural works, such as concrete, cheap wood, Euro-pallets, textiles, kitchen laminates, wax, fabricated or found metal sheets, raw linen, metal mesh, found cardboard, and even butcher paper, although the same works refer to the disembodied digital world, its languages, and its landscapes. There seems to be no opposition, nor rejection implied in his stance, and yet to “dumb down” what is supposedly immaterial and perennially in flux is another way to hammer at the rhetoric of the New Media. And when Boot resorts to traditional media, such as paint on canvas, to portray the digital worlds, for instance with the series of “Japanese/Google landscape paintings” (like Phillip Island,

Raper Street,

Raper Street, and Macleay Street,

and Macleay Street,  all 2016) his “Platz, platz” seems slightly more sardonic. “I first became aware of Japanese landscape painters by an interview of the Australian artist Brett Whiteley, whose use of color I’ve often found amazing. He discussed how some Japanese painters would paint the landscape by studying it in depth, by being present/ within/walking in the landscape, and only pick up a brush when they went back in the studio,” Boot says. “The color palette [of the Google landscape paintings] is inspired by Google image searches. While buffering, all images are reduced to a representative color, so that the palette is somewhat an archetype of the search—perhaps a good connection to how information is repeated within our collective (and varied) filter bubbles. By reproducing that palette, I am painting places where I have ‘walked.’ Colors are perceived subjectively and reflect our physical surroundings, but that’s not necessarily true for the digital sphere, elaborated by machines.” Painting here might be seen as a travelogue of the artist’s site visits and “walks,” slowed down to the point of stillness.

all 2016) his “Platz, platz” seems slightly more sardonic. “I first became aware of Japanese landscape painters by an interview of the Australian artist Brett Whiteley, whose use of color I’ve often found amazing. He discussed how some Japanese painters would paint the landscape by studying it in depth, by being present/ within/walking in the landscape, and only pick up a brush when they went back in the studio,” Boot says. “The color palette [of the Google landscape paintings] is inspired by Google image searches. While buffering, all images are reduced to a representative color, so that the palette is somewhat an archetype of the search—perhaps a good connection to how information is repeated within our collective (and varied) filter bubbles. By reproducing that palette, I am painting places where I have ‘walked.’ Colors are perceived subjectively and reflect our physical surroundings, but that’s not necessarily true for the digital sphere, elaborated by machines.” Painting here might be seen as a travelogue of the artist’s site visits and “walks,” slowed down to the point of stillness.In “Painting Beside Itself,” published in the journal October in the fall of 2009, David Joselit explains how “transitive painting ... invents forms and structures whose purpose is to demonstrate that once an object enters a network, it can never be fully stilled, but only subjected to different material states and speeds of circulation ranging from the geologically slow (cold storage) to the infinitely fast.” In a conversation with David Andrew Tasman, published on DIS Magazine (dismagazine.com) in March 2015, Joselit further clarifies his position:

The artwork almost always contains vestiges of what might be called the roots—or infrastructural extensions—of its entanglements in the world. These might include the means of production of the image, the human effort that brought it into being, its mode of circulation, the historical events that condition it, etc. The artwork’s format solidifies and makes visible that connective tissue, reinforcing the idea that the work of art encompasses both an image and its extensions. The term format does not merely distinguish between digital vs. analog, as medium might do, but points to how an image is situated within a set of relations that condition how efficacious it may be. Formats attract attention and exercise power. The difference between format and medium lies largely in the heterogeneity of the components—aesthetics, data, history, the scene of an action—which is anathema to traditional concepts of medium. When Bruno Latour talks about assemblages, he is talking about linkages—not the abstract infinity of a network. It’s difficult to quantify the limits of extension, for instance, one must think about what is folded into images as well as what extends out from them.

Boot works constantly on formats and circulation, as well as on possible ways of crossing the bridge between digital and analog art production. With fellow artist Valentin Ruhry, also based in Vienna, Boot operates the online platform cointemporary.com, which introduces to the public a selection of digital artworks, including editions—one at the time and for a limited amount of time—that can only be purchased in Bitcoin (MAK in Vienna acquired a piece, and it was the first museum to do so). Cointemporary has also facilitated discussions and meetings on topics such as digital information distribution and the blockchain, which is now one of Boot’s main interests. He’s been designing new 3-D modeled “smart” sculptures as well as the distribution of their digital files via blockchain, so that the same work can exist and travel IRL as well as online. “The structure of the blockchain allows for a decentralized exchange. I am particularly interested in Ethereum-based cryptocurrencies and their varied use cases. I read a good analogy: that Bitcoin is the coin, and Ethereum is the hammer. With Ethereum complex projects can be built . . . and the Internet will morph into something completely different (no idea what that will be),” he told me.

Art and market spend a lot of time in bed together lately, while algorithms work feverishly at the construction of art value, artists’ rankings, celebrity status, and augmented visibility. Blockchain is a new digital infrastructure, built with “solid blocks”— architectural metaphors back in play—that are bound to impact the physical world, and especially the space of our lived environment because of the Internet of things. The blockchain’s promise of absolute traceability and permanent resistance against the alteration or destruction of data should be granted by decentralized consensus and the absence of a centralized server. Its perceived utopia (or potential dystopia, according to other views) also reminds us, I think, that the digital “environments” that we’ve built so far are not really open, nor really public, and that we’re not always free to choose or to control what circulates in them, let alone what images—while the movements of people and bodies across borders and countries, on the other hand, are increasingly monitored, filtered, and controlled. Let’s hope that we’re not really ready to sit down and obey just yet.

Letting It Drop

Elisa R. Linn

In casual conversation “spam” means very different things at different times, though mostly tinged with mendacity or misconduct. As a vague noun, its use can easily slide into what is known as the “paradox of the heap.” Collective and singular, “spam” can mean all the (spam) messages one has received or it can refer to one particular e-mail. The code that camouflages a spam mail so it can enter our inboxes is often dubbed “spaghetti,” implying twists and turns that flagrantly violate the principles of structure. Firewalls and filtering programs do not just casually ignore “spaghetti,” they do not even recognize it in the first place. Although distorted or patterned by image interference, these montages form convoluted pictorial compositions, while carrying out a flat, sometimes mindless message on their surface: “cures baldness!”; “quick loans!”; or “horse kicks Harrison Ford in stomach!”

Could programming (the tool to code and decode “spam” and “spaghetti”) be referred to as a gesture? Could it be something in between making and writing, something that, to echo Vilém Flusser, involves the dialectical movement of informing, transforming, or moving matter with power, a free expression of an inwardness, that possesses the ability of deception?

In Andy Boot’s noodle paintings one might recognize precisely the act of programming as a sort of gesture. Boot’s paintings can be considered as a way of conceptual thinking situated where semiotics interferes—abstracting lines from surfaces and decoding them. Boot dissects and synthesizes the tactical and complex striking aesthetic obscuration that spam e-mails and their image attachments are provided with—by tossing color-impregnated noodles on canvas.

In his work Yellowbird (2015),

shown at Minerva in Sydney, the colored traces of noodle-tossing appear like dispersed ribbon worms in yellow, red, orange, purple, green, or blue, marking a vigorous and staggering existence. While operating autonomously these wormy shapes still seem to make use of their potentiality of swarm intelligence—holding connections to one another between several planes of a picture and sprawling within the limited space of the canvas. These filigree painterly marks wave consciously irresolute between micro and macro: depicting merely a detail section of a larger whole and at the same time the painting as an entirety.

shown at Minerva in Sydney, the colored traces of noodle-tossing appear like dispersed ribbon worms in yellow, red, orange, purple, green, or blue, marking a vigorous and staggering existence. While operating autonomously these wormy shapes still seem to make use of their potentiality of swarm intelligence—holding connections to one another between several planes of a picture and sprawling within the limited space of the canvas. These filigree painterly marks wave consciously irresolute between micro and macro: depicting merely a detail section of a larger whole and at the same time the painting as an entirety.Any belief that these color drips could possibly form a recognizable, regular pattern through their repeated appearance is dispelled. This effect can also be seen in another work by Boot titled Consumed (2015),

which was presented in the same exhibition. Here, the marks appear to be caught in an everlasting state of becoming, of coming into shape and collapsing out of it, like a fluid dance of energetically charged particles whose intertwining and pathways call to mind the paths of particles in a bubble chamber. This is like visualizing a momentary “passage” of particles. In the works, projected paths mark the transfer of pre-existing information rather than the production of new information itself. By physically veiling paint on the ground, “passage” allows signs to be convertible, like heterogeneous articulations evolving in real time, in which a variety of senders and receivers, channels and modes of connection arise and suspend.

which was presented in the same exhibition. Here, the marks appear to be caught in an everlasting state of becoming, of coming into shape and collapsing out of it, like a fluid dance of energetically charged particles whose intertwining and pathways call to mind the paths of particles in a bubble chamber. This is like visualizing a momentary “passage” of particles. In the works, projected paths mark the transfer of pre-existing information rather than the production of new information itself. By physically veiling paint on the ground, “passage” allows signs to be convertible, like heterogeneous articulations evolving in real time, in which a variety of senders and receivers, channels and modes of connection arise and suspend.The pictorial effectiveness of these paintings arrives through its moves. It does so by balancing and unbalancing, disrupting and restoring—to put it briefly: by adopting principles of chaos dynamics that are impossible to be fully tracked by the viewer for whom the work keeps a fantastical arena of get-togethers incoherent. Those complex, even “chaotic systems” can have few interacting subunits, but produce very intricate dynamics. Known from nature, the neural networks of the brain, or Internet traffic, chaotic systems show certain typical behavior patterns despite their long-term unpredictable and seemingly irregular behavior.

In the case of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, physicist Richard Taylor began to notice that the drips and splatters on the artist’s canvases seemed to create repeating patterns at different size scales—just like fractals, regularities that are self-similar on finer and finer magnification.1 On the basis of fractal measurement, Taylor later helped collectors to reveal fake versus authentic Pollocks in circulation.

In Boot’s paintings a twisted aesthetic order, from the look of accident, might resemble Pollock’s drip paintings that art critic Emily Genauer once demonized as “a mop of tangled hair I have an irresistible urge to comb out.” 2 Both lack any obvious principle of organization, and their internal logic does not reveal itself at first glance. In Boot’s case the outcome always depends on the technique and chance location of the thrown noodle, and of course also on the individual noodle as a middleman, its texture. This “all-over” method gives the impression of being chaotic and promises an order out of mechanical routine—only to betray it. Here randomness is married to repetition, where impenetrability is elevated to a characteristic structure, a signature, calling its substructures arbitrary, describing the variations, changes, and alterations vaguely ephemeral.

To stay with Pollock, the reconceptualization of painting from the surface as a “window on the world” to the relationality of seemingly haphazard physical and metaphysical forces went hand in hand with his removal of the canvas from the vertical plane of the wall to the horizontal plane of the floor. In a similar way, but rather heaving objects on the painting, and through that, leaving an epoch behind, Duchamp demanded a horizontal relationship between the artist and the artwork. He did not express “movement” as kinetic or dynamic moments, however, but rather as cuts of time that bear witness to the idea of movement as traces—something that he would call “pictorial nominalism”—and made works of art that serve as a documentation of experimental assembly. One truly surreal experiment by the artist was to let three threads of one meter each be dropped from a height of one meter onto three different canvases in order to fix the accidental forms which are quite different from case to case—an instance of “canned chance” that Duchamp used for creating the work Three Standard Stoppages (1913–14).

Duchamp himself saw this type of active passage from one to the other taking place in the “infra-thin,” a notion that explains itself rather through illustration than a definition: “Fire without smoke, the warmth of a seat which has just been left, reflection from a mirror or glass, watered silk, iridescent, the people who go through [subway gates] at the very last moment, velvet trousers, their whistling sound, is an infra-thin separation signaled.” 3

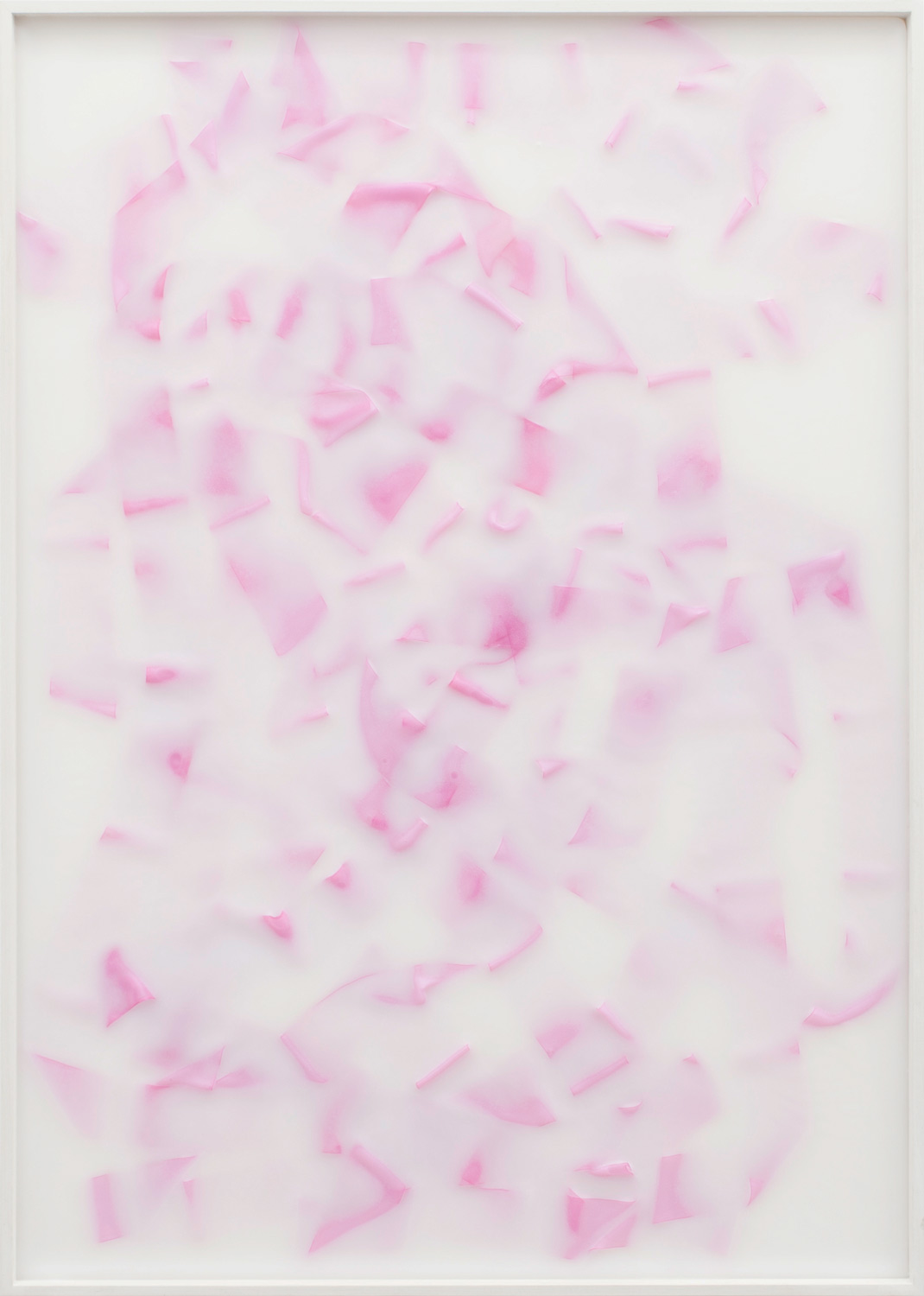

Boot subtly addresses this question of how objects can become artistic out of almost anything by literally reconstructing the act of letting something fall into the picture as such. Boot here links up to a self-aware handling of decisions, coincidence, and repetition through shaping the final form of his work. And this is precisely where “passage” emerges, i.e., in the behavioral shape between things. This happens, for example, by repeatedly letting pink, blue, or purple gymnastic ribbon bands drop into picture frames and fixing them with dried white wax, as in his earlier works Untitled (navy blue)

and Untitled (pink)

and Untitled (pink)  (both 2012).

(both 2012). The act of falling resists the bands’ initial purpose to accompany and perform rhythmic movement patterns. The solidified wax ultimately forces the object and its three-dimensional arrangement into a two-dimensional transmitted image of a pattern whose optical appearance fluctuates. Boot has broken down the proverbial walls of what is appropriate to display in a frame and one might wonder if one is tricked into seeing a flat patterned surface with a slightly Op Art touch or a topographical relief.

Boot’s works resist any sort of transparency, instead, they are elusive, and keep the observer first of all at a distance—which has the effect of making them more enticing. Dealing with physical and virtual notions of absence and presence, however, they still count on the viewer’s inclusiveness. Thinking of artworks as walking through an entrance, when you see it the first time, and an exit, when you stop thinking about it, it seems as if Boot’s noodle paintings and works of ribbon bands in wax provide a hospitable stay and never too hastily show you the door.

Unconcerned that the works might play with clichéd attributes of the avant-garde, and with a little ironic overtone, Boot appropriates the ingenuity of Pollock’s drips and tackles the redefinition of the readymade’s meaning (after Duchamp)—and by this action orchestrates works as mediums of communication. In these works by Boot the viewer is finally constructing the images, illustrating the Duchampian dictum that the work becomes the point of departure, an agent to invent another work.4 Here, art does not emerge as a contest for the most original idea. What if art is an autonomous language, which evolves in any case and thereby occupies the artist-subject only as a “host”?

This leads us back to the notion of programming: if one plays programs enough, realizing all their coincidental combinatorial possibility—even the most unlikely—they become toys.5

As Chus Martínez argues, drawing from Flusser, what underlies our entanglement with technology is fundamentally ambiguous, for as much as we wish software and machines to reduce the level of skill required to carry out a job and eventually free us from unpleasant work altogether, we fear this kind of deskilling at the same time.6 What is inherent in this thinking is a dream of an enhancement through artificial life that stems from a modernist approach towards technological progress. But a true fusion of two entities, the human and the artificial, is beyond a hierarchical understanding of one becoming only the tool for the other or that one suffers because of the emergence of the other. The acceptance of alterations and the merging of orders, as well as the coexistence of codes, continue to be a problem to the extent that a rigorous engagement with hybridity still remains out of sight. But hybridity might be understood as a return towards experimental conditions. This transition will be challenging as our prevailing interest is focused on the definition of steps that lead to results rather than the “educts,” meaning the forces that motivate and enable the experimentation in the first place. As Martínez further argues, art should be the site for an ongoing effort to create these experimental conditions.

While looking at Boot’s noodle paintings and his rhythmic gymnastics ribbon works, significant surfaces on which elements act in a magic and technical fashion towards one another, they seem to spur the viewer’s mind to consider what Flusser understood as the potential of freedom: the question of whether one might succeed in mastering the code (of “spam” and “spaghetti”) and find new possibilities of the program. Or to put it prosaically, can we find the ability to rule the apparatuses instead of letting the apparatuses rule us.

Notes

1. Richard Taylor, “Order in Pollock’s Chaos,” Scientific American, vol. 287 (December 2002), pp. 116–21.

2. Emily Genauer, “This Week in Art,” New York World-Telegram (June 16, 1945).

3. Marcel Duchamp, Notes, arranged and translated by Paul Matisse (Boston, 1983), p. 45.

4. Octavio Paz, “The Castle of Purity,” in: Marcel Duchamp: Appearance Stripped Bare (New York, 1978), p. 86.

5. Vilém Flusser, Medienkultur (Frankfurt am Main, 2002 [1997]), p. 24.

6. Chus Martínez, “The Complex Answer,” Berlin Biennale text (2016).

Backgrounds, Surfaces and Landscapes

Chris Sharp

The title of this book purports to present three distinct parts of seeing, three distinct zones or planes integral to the organization of an image. As if each part could be localised and individually demarcated as independent, albeit no less contingent upon the other. Background. Surface. Landscape. Like a puzzle, how do all these pieces fit together? The background can be found somewhere beneath the surface of the image, which itself is a landscape. Or maybe a landscape is actually the background to an image indistinguishable from its surface? But in a world of surfaces, a world either being constantly pushed up or flattened to a surface of, say, a screen, where does the surface begin and end? Is there even a surface any more? Does not the word “surface” become redundant, tautological? Perhaps more insistent than that question is the ontological status of the image. If there is nothing but surface, a world composed of sheer façade, then that would mean that there is nothing but image – the “content” of that unbroken, unilateral, unending virtual veneer (that which becomes labyrinthian by virtue of its totality, of there being no way out) – at which point the word image itself, and its constituent elements, borders on a similar redundancy. In such a totalizing context, an interesting Duchampian question comes to, alas, the surface: just as Duchamp once asked himself if it was possible to make a work of art that was not a work of art, the Vienna-based Australian artist Andy Boot asks, all but rhetorically, not to mention paradoxically, if it is possible to make an image that is not an image. Indeed, what constitutes an image now that we live in the labyrinth of images? What is its current zero degree? And how is that determined? Or perhaps better yet, legislated?

It happens that Boot had a few of these questions answered, at least provisionally, when he became fascinated by a certain kind of confetti spam. In this form of spam, a layer of digital confetti is discreetly superimposed upon an advertisement (Viagra, etc), seeking to ensure that the layer does not interfere with the legibility of the message. Superficially transformed into an image, the spam camouflages its actual content and is therefore granted the privilege of circulation (if it sounds like a reverse allegory of the history painting, that’s because it probably is). By way of addition, a specious act of subtraction is effectuated, which in turn, permits an unquantifiable multiplication of “information” to take place.

Inspired by such arbitrary zero-degree image legislation, Boot wanted to see what would happen if he applied the confetti technique, as it were, to his own practice, which he did in a series of paintings, works on paper, and even sculptures. The works on paper wield the paradoxically significant title Backgrounds (2010–). These consist of framed pieces of paper, whose surfaces have been sparsely riddled by series of all over multi-coloured, if slightly antic, worm-like marks (if they seem antic or gestural, it’s because the artist availed himself of the novel technique of spaghetti tossing in order to achieve the desired effect). To describe these works as backgrounds which have been pushed up to the foreground would be more incorrect than correct, because, in the end, what they do is shuffle such issues off to the side. In a further, say, double twist of the screw, Boot transforms this all but invisible, zero degree image into something visible, while depriving it of its original purpose, which is to act as a smuggler of textual information. If here the artist neutralises such image legislation by rendering it visible, in Surface (one) 2010, he also begins to disclose just how potentially sinister it is. In this work, Boot visibly concealed a confetti painting, like a tablecloth, which was overlaid with glass, on the desk of Croy Nielsen gallery. Inconspicuously incorporated into its environment, the work inevitably alludes to a phantasmal totality, of what could be called the invisible, omnipresent labyrinth of images. And yet, given the festive and antic nature of these marks, such a minatory appraisal of the ontological status of the image is not without a sense of humor. Take for instance Untitled (2010). One of the more ridiculous yet endearing pieces from this body of work, this forlorn sculpture/painting consists of a small, ratty swath of canvas, bearing a single confetti mark, placed at the head of a tubular segment of black rubber, itself held in place in a small, round foundation of concrete, like a buoy. Reduced to a semaphoric minimum, this trace seems intent on claiming its place among the labyrinth of images, despite its ostensible lack of intelligibility. Anxiously signaling, its presence is assured not just by its support, but more importantly through a virtual absence, which surrounds and extends beyond it, in every direction.

As much could be said to happen in the image of the sea in Boot’s Stella di Mare (2011), which consists of an approximately two and half by two meter image of a sun-mottled portion of seascape applied to a wall like wallpaper. Presented as such, the depthless light of playing on the sea’s surface tends to collapse the space inside the image, pushing its contents up to its surface. As if it, the sea – which here becomes a metaphor for the image, a sea of images – could break through and come flooding in, surrounding us on all sides, like a labyrinth. Even though it already has.